Research overview

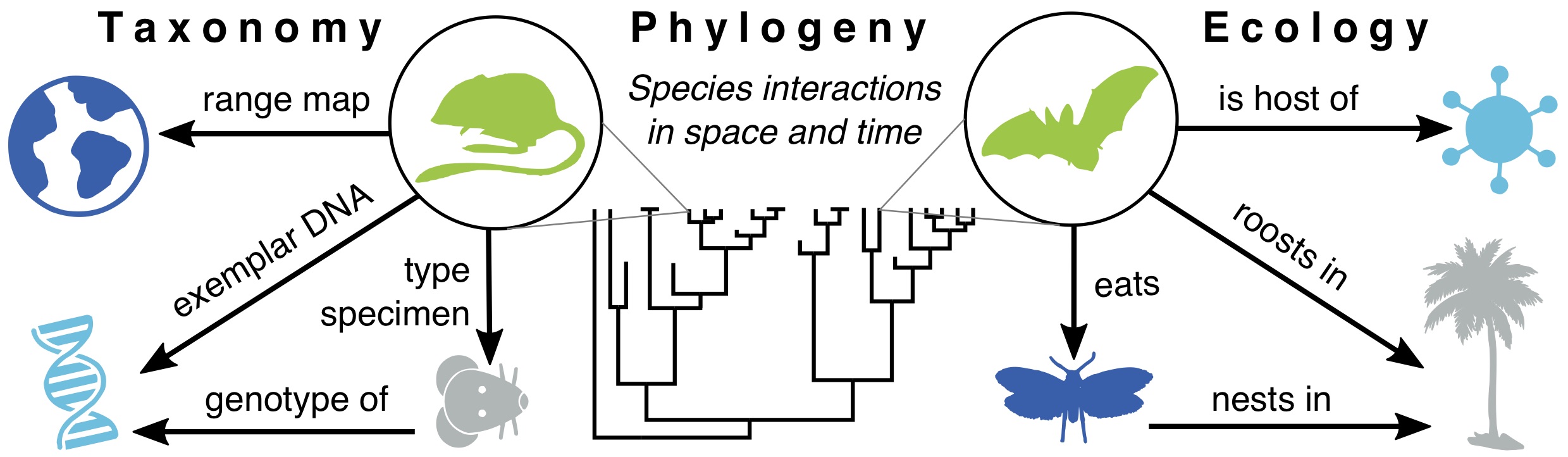

My research group embraces the urgent need for mammal phylogenetic ecology, which we frame as the application of phylogeny-informed taxonomic knowledge to the study of species ecological interactions. More colloquially: Know your species and their history to ask how and why organisms interact.

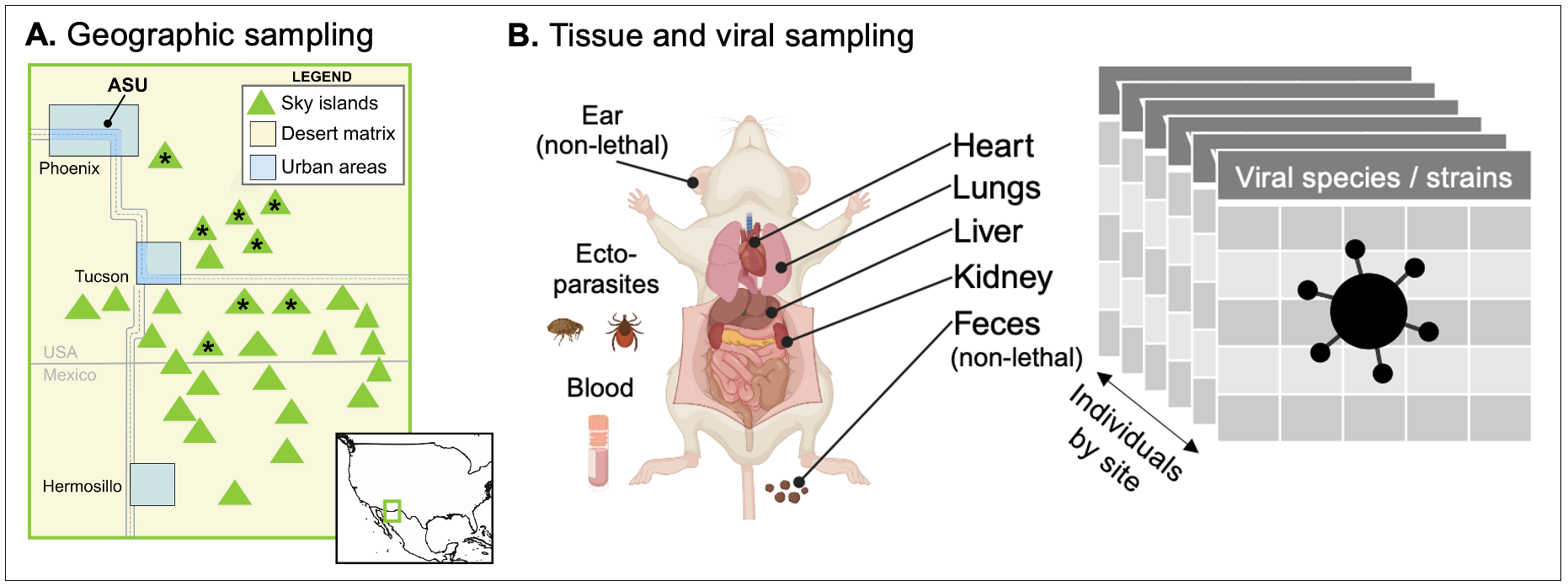

Our integrative specimen-based research unites organismal, genomic, computational, and synthetic approaches to study eco-evolutionary processes. Why specimens? Well, preserved natural history specimens (including frozen tissues, skins, skeletons, endo-/ecto-parasites, blood, feces, and fluid-preserved whole organisms) are nothing less than the physical basis for our collective knowledge of Earth's biodiversity. Every data point in public databases like GBIF or GenBank comes from some organism — however, only the fraction of observations that are preserved as specimens are available for future workers to gather now-unimagined data. Our lab contributes to growing this 300-year record of the natural world while using it to query the processes under which biodiversity was generated.

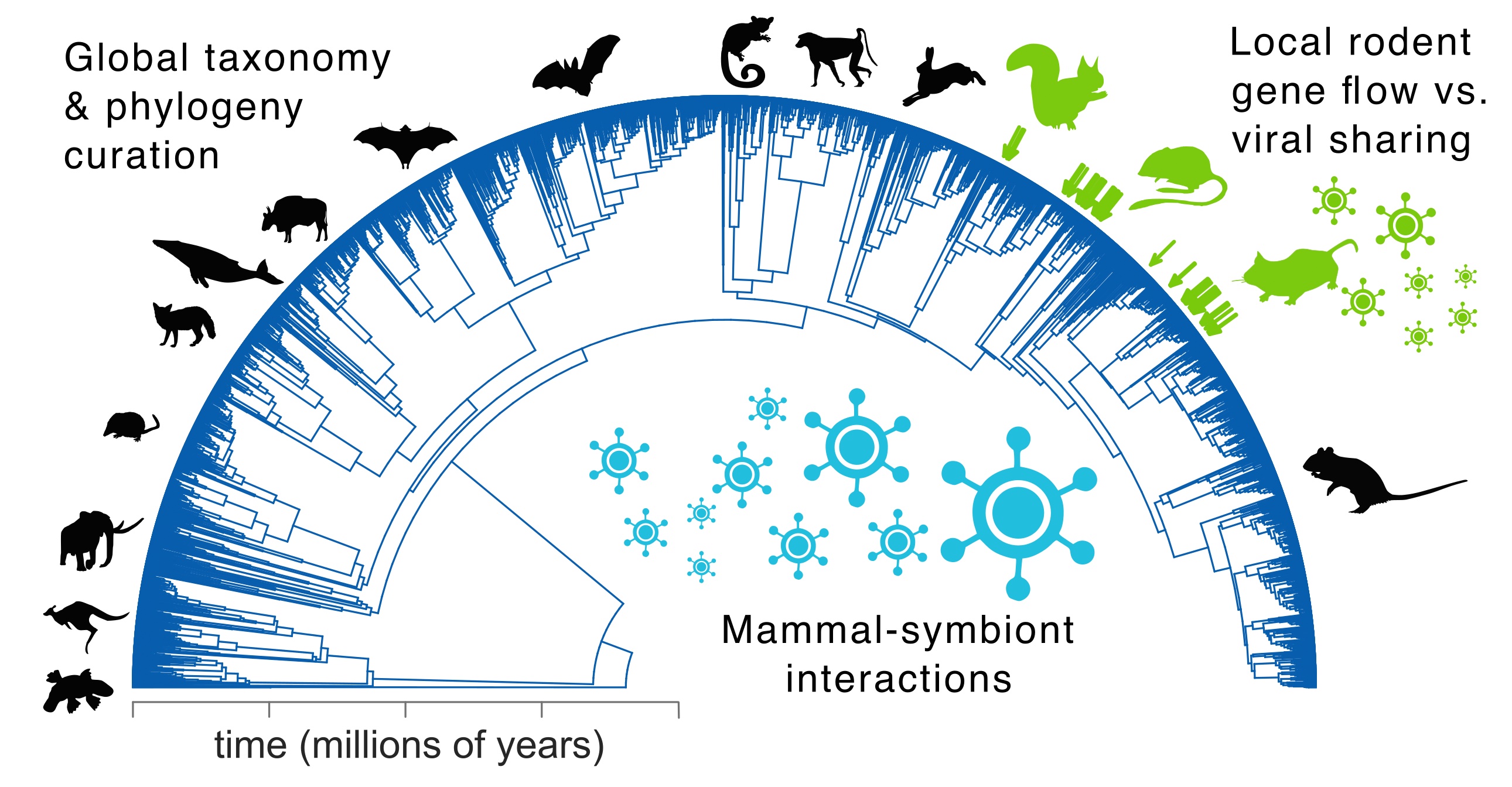

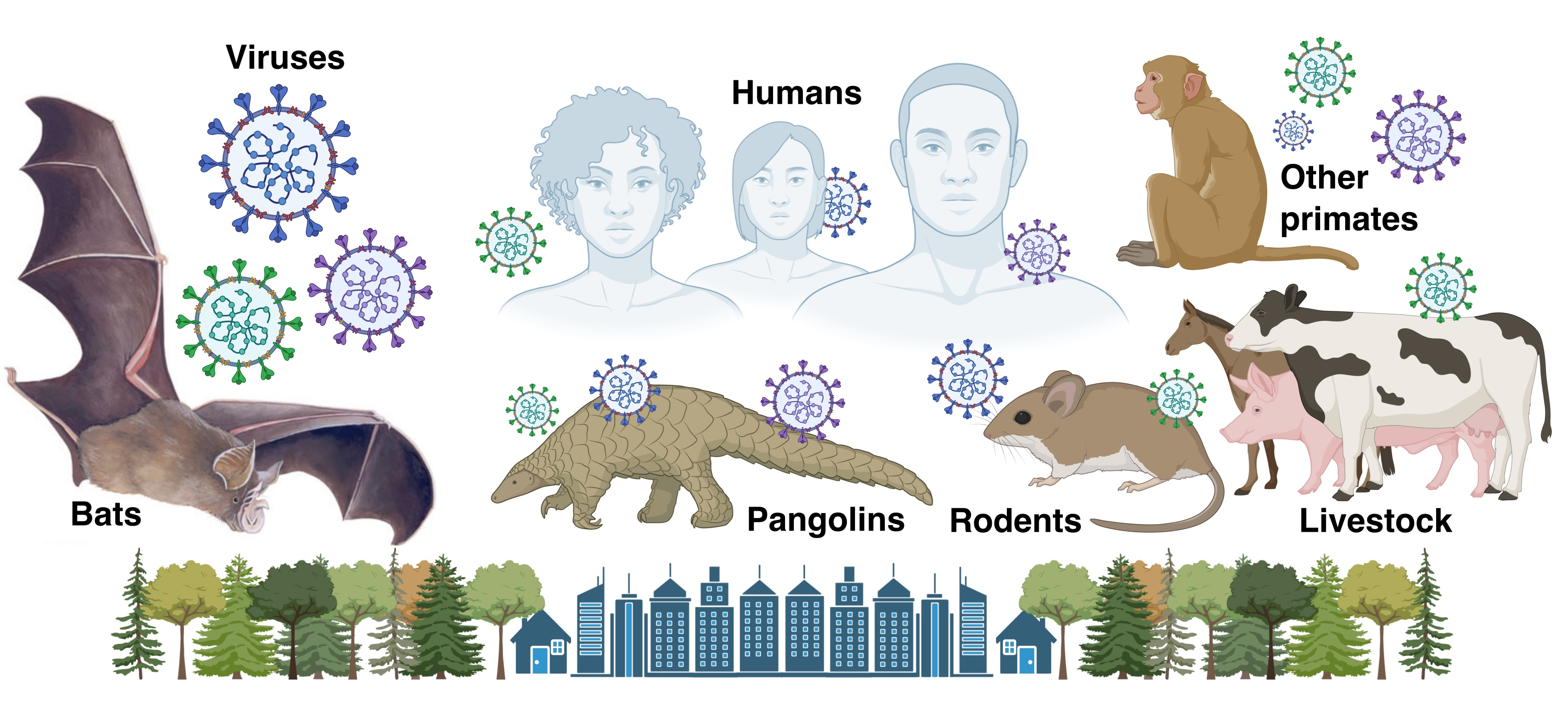

Projects at global to local scales. We engage in a range of interdependent activities to investigate the evolution of species interactions in wild mammals, including fieldwork, biodiversity genomics, phylogenetics, and large-scale data integration (see below; green arrows highlight native Arizona species; silhouettes from phylopic.org or open fonts). This work aims to build both digital capacity — integrating silos of biodiversity and biomedical knowledge — and physical capacity via the holistic collecting of natural history specimens. By unifying perspectives across scales, our research advances understandings of eco-evolutionary processes spanning from speciation to viral spillover.

Types of questions we ask [and some related projects]

1. What are the species in a clade or region, and how do they interact? (taxonomy and biodiversity data)

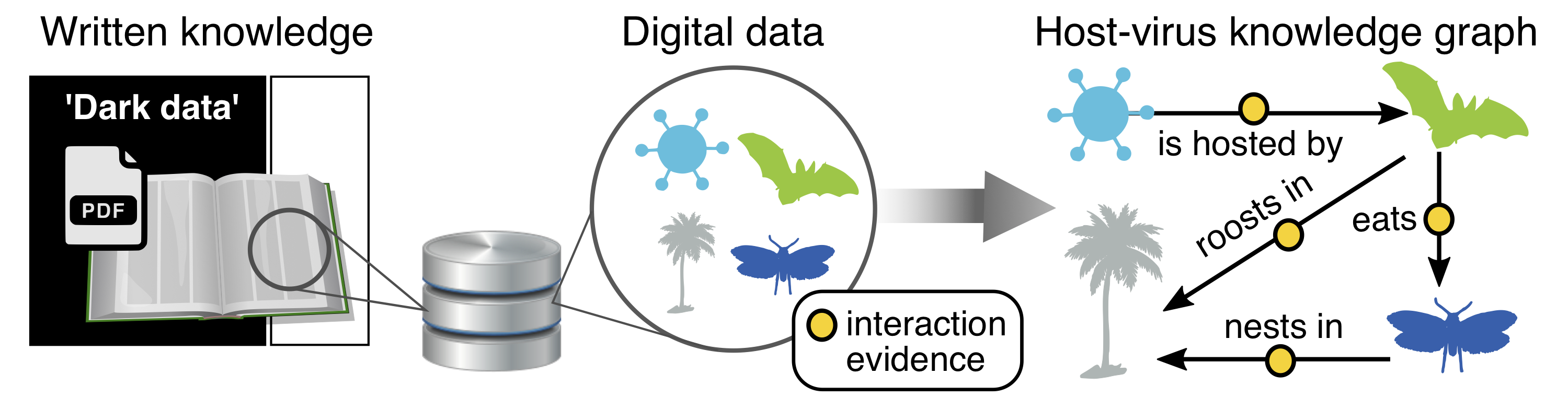

Species are at the core of all biodiversity science — circumscribing which species are present is the baseline for studying patterns of ancestor-to-descendent relationship among those species, and, in turn, the historical processes that produced those divergences. Species names are just the beginning: the meaning of names varies widely depending on which data are considered by which authors, so careful data synthesis is often needed. In our lab, we do both species delimitation at a local-to-regional level (e.g., analyses of gene flow, phylogeography) and species synthesis globally (e.g., curating data on genetic relationships, geographic ranges, ecological traits, and their taxonomic history). This includes recording known observations of species interactions, including host-virus data and the evidence of that interaction. Doing this work requires improving upon the mammal tree of life, including the development of more sophisticated tools for updating the species name labels for the millions of primary-source observations in global databases (e.g., GBIF, GenBank). It also requires new tools for mining interaction data from published literature, which was the focus of our 2021-2023 NIH R21 grant.

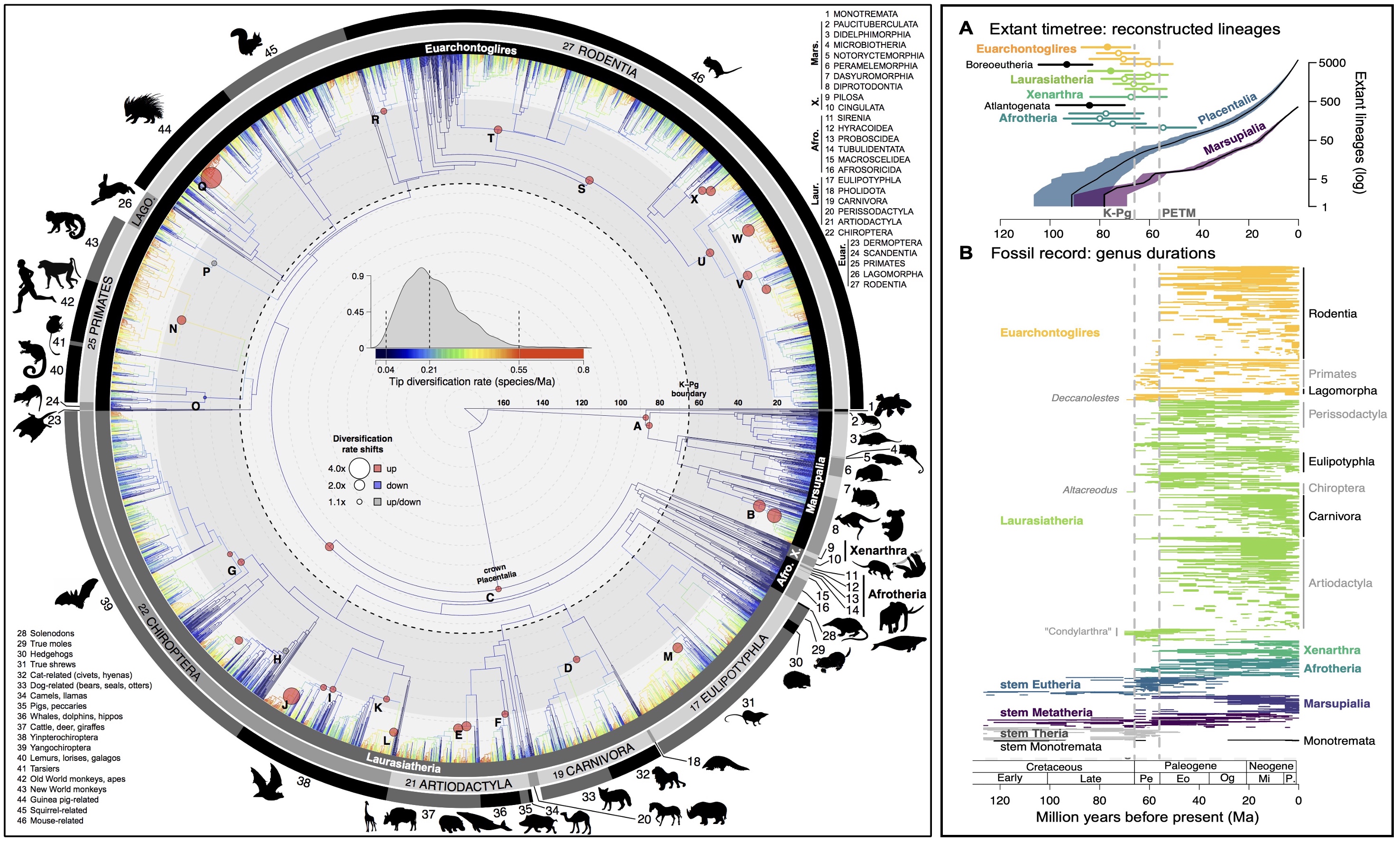

2. How fast are lineages diversifying? (phylogenetic rates and gene flow)

Estimating the timing and rates of past evolutionary events allows for testing which concurrent events or processes may have caused rates to vary. Fossils are the primary means by which we anchor the relative divergence times (estimated from homologous genetic or morphological changes) into absolute time of years. Mammals, and especially rodents, have well-studied fossil records that allow us to reliably root our genomic analyses in the timescale of earth-history events. The dual importance of fossil and molecular insights is increasingly recognized; extant-only phylogenies cannot tell us everything we want to know about the past, but they can tell us about processes near the present day (often moreso than fossils). Our work has shown that while fossil rate signatures are absent from older lineages of the extant tree, lineages younger than 10-million years (Ma) are unbiased. Thus, there is considerable promise in continuing to integrate fossil, molecular, and ecological trait data (e.g., proxies of body size, feeding mode, or vagility) into studies of eco-evolutionary dynamics. We are investigating how rates of speciation, extinction, and trait evolution vary relative to their population-level covariates of gene flow or isolation to better understand these processes.

3. By what ecological and genomic processes? (comparative methods)

The genomic consequences of species interactions with other organisms (biotic) or the environment (abiotic) are at the core of what our lab aims to investigate, but we recognize that doing so requires reliable answers to questions 1 and 2 above. For this reason, we move forward on all three questions jointly, using an iterative approach to advance the field in all areas. In our lab, we are focusing on two main areas currently:

- Mammal comparative genomics. Which mammal species have sequenced genomes? And what common properties of these genomes tend to emerge among lineage with similar ecological modes? We are investigating these questions both globally and locally, especially in desert rodent lineages.

- Intrinsic species-level traits. How do traits like living underground, or flying, or having 12 mammae instead of 4 influence rates of gene flow or isolation, and lead to trends of speciation and extinction? We are currently studying these dynamics among global mammals, but there is ample fodder for more regional investigations.

Other projects — biodiversity data liberation, island extinctions

Understanding the Earth's biodiversity is more important than ever. Yet sharing basic knowledge about biodiversity is currently far too difficult, representing a key roadblock to scientific progress and informed policymaking. The published research and observations of scientists worldwide – spanning, from species distributions to traits and interactions – are too often locked in disconnected and inaccessible literature. Opening up what is known about biodiversity from publications within a network of connected, curated, and digitally accessible knowledge bases is therefore a fundamental challenge for the global research and policy communities to address.

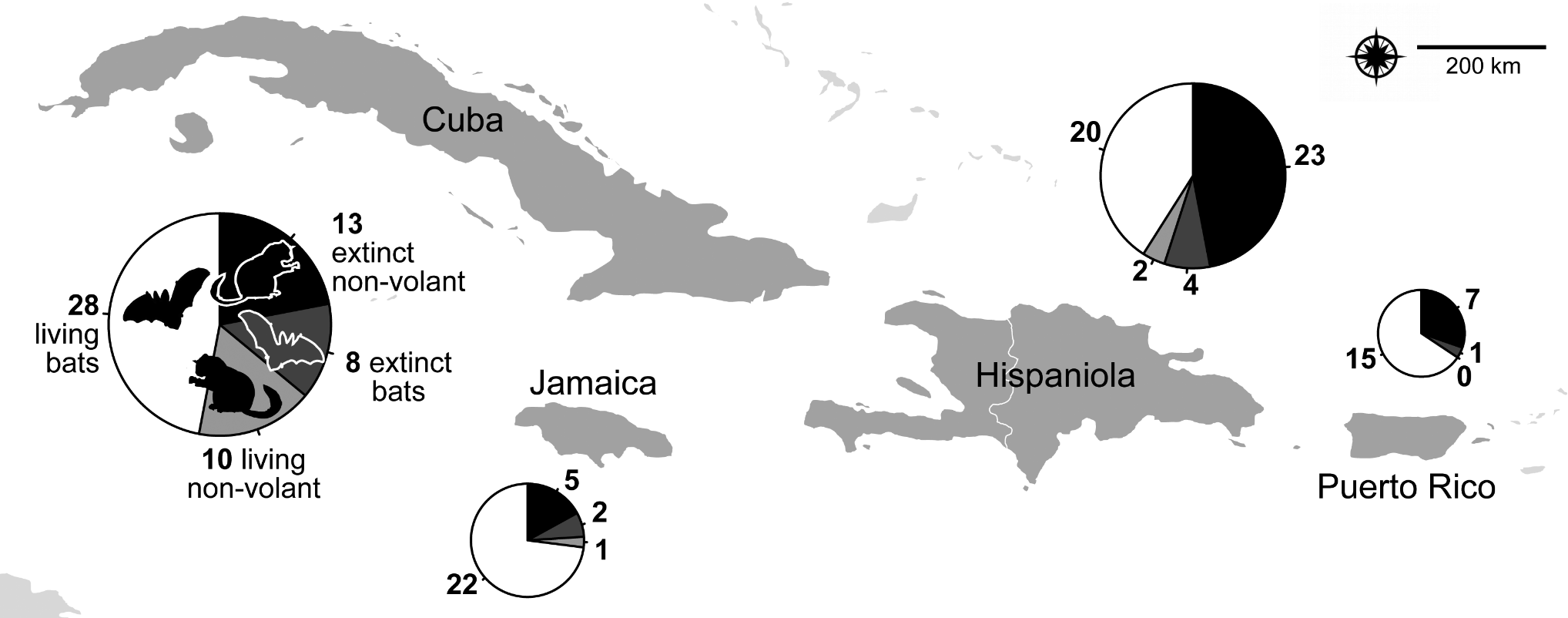

Mammal extinctions have been greater in the Caribbean archipelago than anywhere globally, yet exactly how many species and their timing of last occurrences has not been well understood. I helped organize a 2015 ASM symposium and a 2019-2021 SESYNC working group to untangle these dimensions, including in other island systems.